Are Evidence-Based Medicine and Public Health Incompatible?

This article by Michael Schulson was originally published on Undark

February 21, 2024 by Michael Schulson

It’s a familiar pandemic story: In September 2020, Angela McLean and John Edmunds found themselves sitting in the same Zoom meeting, listening to a discussion they didn’t like.

At some point during the meeting, McLean — professor of mathematical biology at the Oxford University, dame commander of the Order of the British Empire, fellow of the Royal Society of London, and then-chief scientific adviser to the United Kingdom’s Ministry of Defense — sent Edmunds a message on WhatsApp.

“Who is this fuckwitt?” she asked.

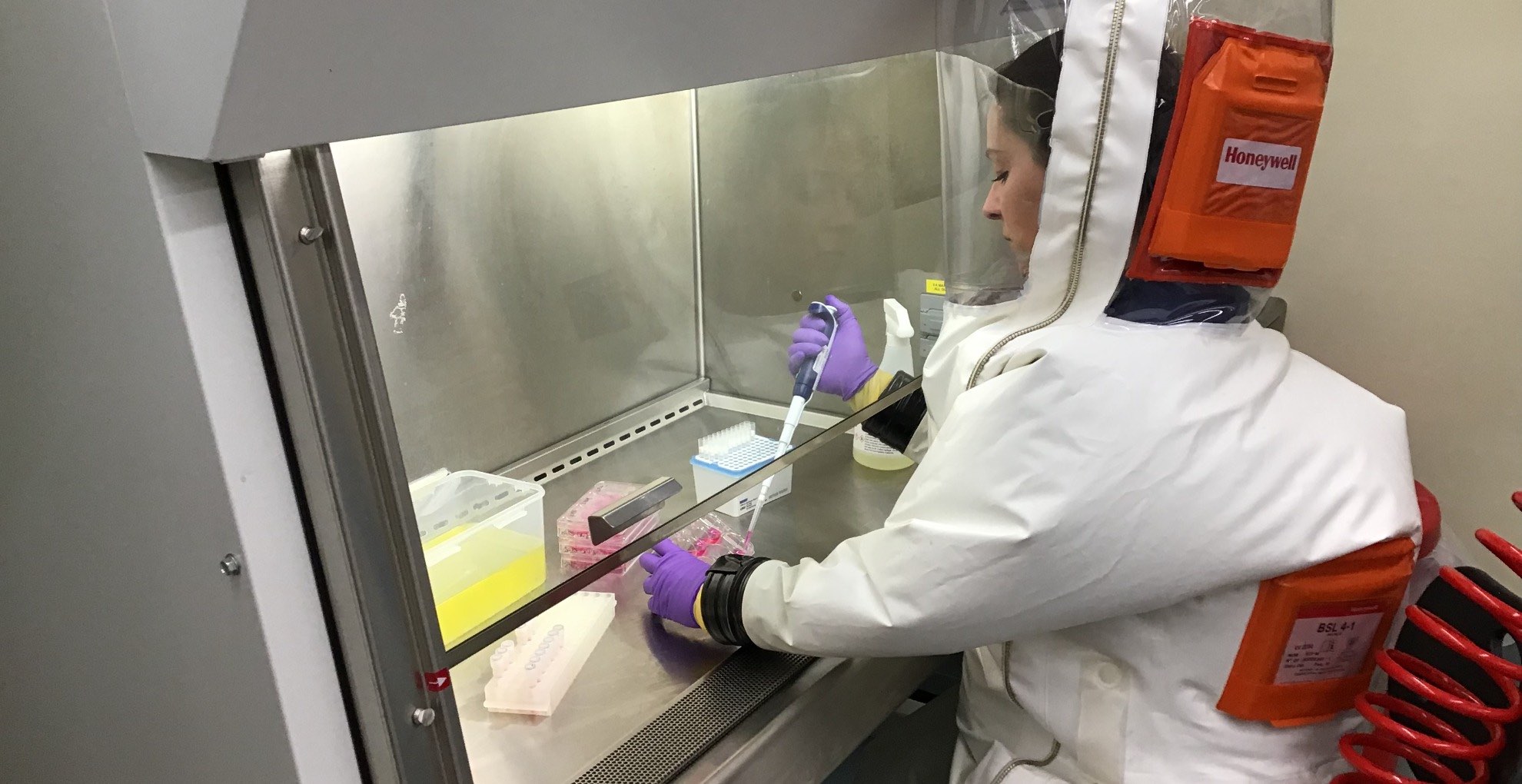

RelatedAmid Covid’s Turmoil, Biosafety Gets Political

The message was evidently referring to Carl Heneghan, director of the Center for Evidence-Based Medicine at Oxford. He was on Zoom that day, along with McLean and Edmunds and two other experts, to advise the British prime minister on the Covid-19 pandemic.

Their disagreement — recently made public as part of a British government inquiry into the Covid-19 response — is one small chapter in a long-running clash between two schools of thought within the world of health care.

McLean and Edmunds are experts in infectious disease modeling; they build elaborate simulations of pandemics, which they use to predict how infections will spread and how best to slow them down. Often, during the Covid-19 pandemic, such models were used alongside other forms of evidence to urge more restrictions to slow the spread of the disease. Heneghan, meanwhile, is a prominent figure in the world of evidence-based medicine, or EBM. The movement aims to help doctors draw on the best available evidence when making decisions and advising patients. Over the past 30 years, EBM has transformed the practice of medicine worldwide.

Whether it can transform the practice of public health — which focuses not on individuals, but on keeping the broader community healthy — is a thornier question. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Heneghan and several other prominent EBM thinkers became influential critics of pandemic policies. The specifics of their critiques vary, but certain themes emerge: Again and again, they have argued that public health leaders like McLean relied too heavily on error-prone models, biased evidence, and simple intuition when making consequential decisions. At the same time, they say, those public health experts did little to gather rigorous data to back up their claims about the usefulness of interventions like mask mandates and school closures.

At stake are deep divisions over how scientific evidence should be used to make decisions.

In response, some public health experts and physicians — including other prominent people in the EBM movement — have argued that researchers like Heneghan and his allies have overstepped their bounds, making unreasonable demands on public health that can be used to further political agendas.

Versions of this debate pop up regularly — over masks, school closures, and even in areas outside of pandemic policy, such as treatment for children experiencing gender dysphoria.

Taken alone, each can be understood as its own little flashpoint. But there’s a bigger debate underway — one that has profound implications for the future of public health practice. At stake are deep divisions over how scientific evidence should be used to make decisions, said Jonathan Fuller, a physician and a philosopher of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “Until we have a better handle on them,” he said, “I think these particular flashpoints are going to keep coming up.”

A foundational tale of the discipline of public health is a story about the triumph of sharp observation. During an 1854 cholera outbreak in London, the physician John Snow mapped the location of cholera deaths in the city. He noticed they clustered around a specific water pump and reasoned — correctly — that the disease spread via contaminated water. It was a lifesaving insight.

In contrast, the foundational tales of EBM are stories of how fallible human observation and reasoning can be. Since at least the 1970s, for example, some physicians observed that women who took estrogen and other hormones after menopause seemed to have lower rates of heart disease. Hormone pills were given to millions of women — at least until rigorous experiments suggested that some women getting the hormone treatments were actually more likely to suffer a range of harms, including heart attacks and breast cancer. (Today, the situation appears more nuanced: Evidence suggests the treatments are safe and even beneficial for some women, but may carry unforeseen risks for others.)

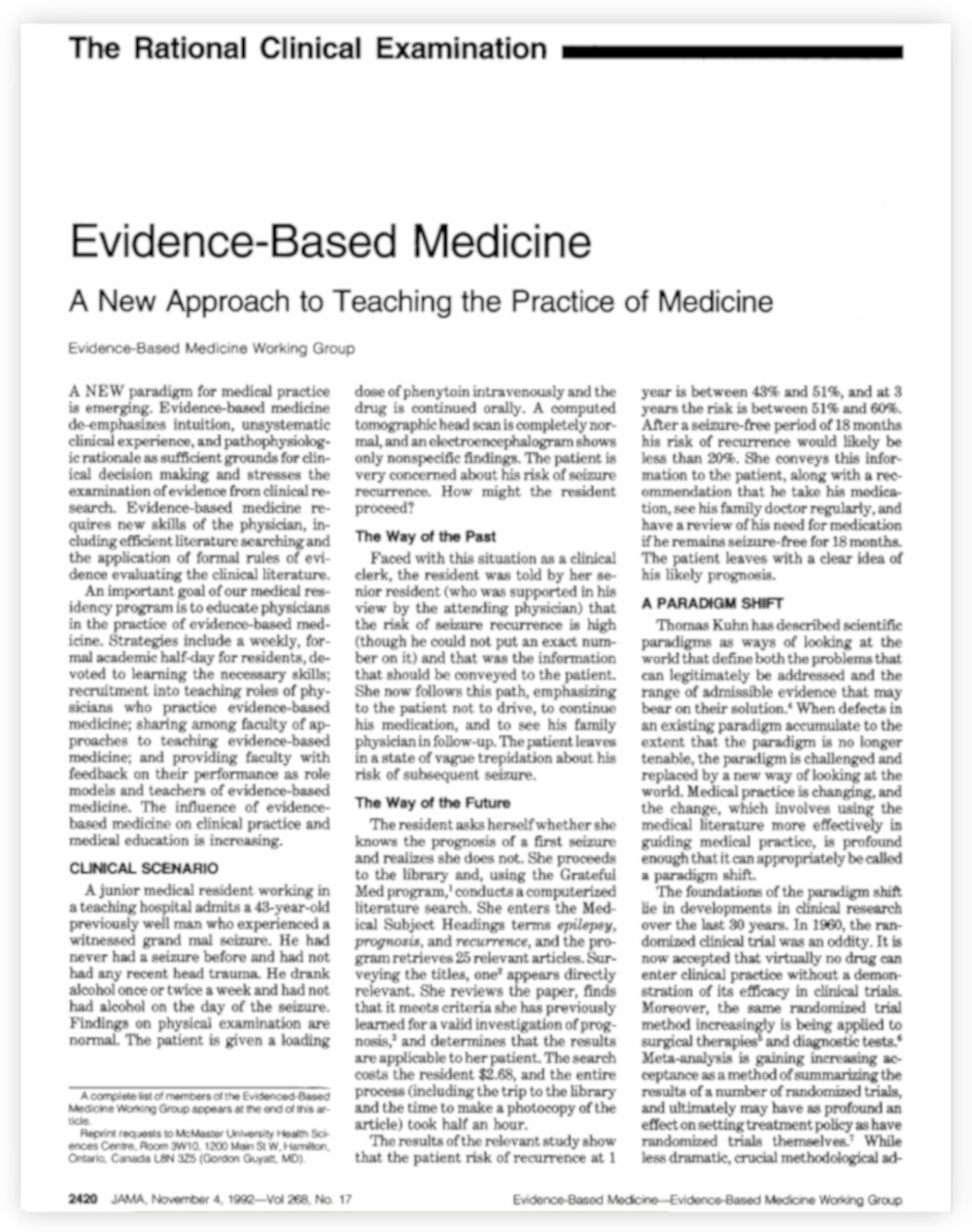

A 1992 paper by a group of physicians spelled out the solution to what they saw as a misguided medical approach — and helped launch the EBM movement. The paper presented a scenario: A junior medical resident sees a patient who has suffered a seizure for the first time in his life. There’s no obvious cause. The patient wants to know the odds that he will have another seizure.

A paper published in 1992 helped launch the evidence-based medicine movement. The authors described “The Way of the Past” and “The Way of the Future” in a scenario in which a patient wants to know what to expect after having a seizure for the first time.

One approach, the group writes, would be for the resident to ask a couple senior doctors to provide her with an educated guess, based on their experiences. Such an estimate is necessarily imprecise. “The patient leaves in a state of vague trepidation,” the group wrote. They labeled this approach “The Way of the Past.”

In “The Way of the Future,” the young doctor skips a consult with her superiors and instead goes to a computer. She performs a search in a database of medical papers, and finds 25 different published research papers on seizures recurrence. She scans through them all, and identifies one that actually collects and crunches data about how patients fare after seizures, providing a more precise estimate of how likely the man is to have another episode. The doctor conveys that risk to the patient, who “leaves with a clear idea of his likely prognosis.”

The goal, the EBM pioneers argued, was to bring the best available evidence more squarely into the practice of medicine.

Perhaps predictably, older physicians were not always elated about a movement devoted to de-emphasizing intuition and “unsystematic clinical experience,” in the words of the 1992 paper. It probably didn’t help that David Sackett, the physician widely described as the father of EBM, seemed to relish challenging authority. “He was a nice guy, but he was in your face,” recalled Jeffrey Aronson, a physician who worked with Sackett in the 1990s, at Oxford. “He didn’t hold back. If he thought you were on the wrong track, he would tell you in no uncertain terms.”

Younger doctors at Oxford, Aronson recalled, seemed to enjoy “something of the iconoclasm that he brought.” But, Aronson added, Sackett “rather raised hackles among the senior members” of the division. (Sackett died in 2015, at age 80.)

Despite that pushback, the movement was quickly influential. But bringing the best evidence into medical decision-making is challenging. There are more than 1.5 million papers published each year in the biomedicine and life sciences, by one recent estimate. Just a single search in a popular database can yield thousands of different studies and analyses. (The figures were less extreme, but still overwhelming, in the 1990s.) How should physicians sift through it all?

To address that problem, EBM practitioners created methods for evaluating the quality of scientific studies. In essence, they were coming up with ways to grade evidence.

Get Our NewsletterSent Weekly

- Email*

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged. Submit

Δ

Say a researcher wants to know whether estrogen hormones prevent heart disease in postmenopausal women. In one kind of study, researchers might explain how estrogen seems to affect the heart, and why it’s plausible that taking hormones would prevent heart disease. EBM approaches would rank that evidence as relatively low quality. Better, according to EBM: an observational study, in which researchers effectively survey women who already use hormones, and those who don’t, to see who has higher rates of heart disease. But even then, there are potential sources of bias: Maybe the kind of people who take estrogen hormones are also the kind of people who exercise more, and it’s actually the CrossFit sessions and the yoga classes — not the estrogen — helping their hearts.

The gold standard for research on clinical interventions, according to EBM, is the randomized controlled trial. In an RCT on the hormone therapy, for example, some women would be randomly assigned to get hormone therapy, some would take a placebo, and then researchers would track their heart health. As a general rule, EBM practitioners have pushed for medical decisions to be grounded in high-quality RCTs whenever possible, rather than in other forms of evidence, even though good RCTs can be slow and costly.

Once doctors have decided how to identify high-quality research, they need some rigorous way of finding all those studies, amid the millions of published papers available. In the 1980s and ’90s, EBM practitioners helped develop something called a systematic review. They would comb through thousands of papers and then use a transparent method to rank all the evidence and synthesize it into a clear, simple conclusion. (It’s basically an exhaustive evidence inventory.) That way, a physician with a question doesn’t have to do all the searching themselves: They can simply refer to the systematic review.

EBM practitioners created methods for evaluating the quality of scientific studies. In essence, they were coming up with ways to grade evidence.

The most influential group that makes such reports is the Cochrane, founded by EBM pioneers in the 1990s. Cochrane has today published thousands of reviews, and they’re widely used to inform medical decisions.

Along the way, the EBM movement also developed a certain culture. “We tend to be skeptics,” said Gordon Guyatt, who coined the term “evidence-based medicine” in the early 1990s, as a physician-researcher at McMaster University in Canada. “It somehow attracts people with a skeptical bent.”

Often, EBM-oriented researchers have directed that skepticism toward medical interventions that, they feel, are based on thin evidence. Indeed, over the years, EBM researchers have challenged certain kinds of cancer screenings, the use of specific drugs for certain treatments, and certain post-operative practices, successfully revising their role in medicine.

“One of the things that evidence-based medicine is kind of pushing back against is an unbridled interventionism,” said Fuller, the Pittsburgh medical philosopher, who has written about the history of the movement. “If the standards of evidence are too low, you’re going to have lots of interventions, because there’s a lot of interested, invested parties that want to sell you things.” Raising the standards of evidence — as EBM aimed to do — will necessarily challenge some of those treatments, he added, and one result is “becoming less interventionist than you would have been before.”

Today, experts debate whether that skepticism toward interventions went too far during the Covid-19 pandemic.

When Covid-19 began spreading worldwide in early 2020, public health leaders were faced with a set of difficult choices: They had very little information about the new virus. At the same time, there was tremendous pressure to act quickly to slow down the spread. Authorities used what evidence was available to make decisions. Computer models suggested that measures like school closure might slow down the spread of Covid-19; schools closed. Some laboratory and clinical evidence suggested masks would slow down the spread of Covid-19; mask mandates were soon in place.

Among researchers, it was no secret that the evidence behind many of these measures was less-than-ideal. Computer simulations are prone to error and fraught with uncertainty. While there was good reason to believe masks could probably slow the spread of the virus, there was inconclusive evidence that masking policies would actually blunt the impact of a pandemic pathogen.

Communities of scientists soon fractured over how, exactly, to deal with all that uncertainty. Already, in the spring of 2020, some evidence-based medicine figures were expressing concerns that public health authorities were acting too aggressively on weak evidence, including models. “The fixation with modelling distracted from an evidence-based interpretation of the data,” Heneghan, the Oxford professor and target of McLean’s WhatsApp epithet, later wrote.

In April 2020, protesters demonstrate against Covid-19 lockdown measures in Miami, Florida. Even in the spring of 2020, some scientists were expressing their concerns that public health authorities were acting too aggressively on weak evidence. Visual: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Social distancing signs are displayed at the entrance to a New York City restaurant in September 2020 as the city continued re-opening in phases following restrictions imposed to slow the spread of Covid-19. Among researchers, it was no secret that the evidence behind many of the efforts to curb the pandemic was less-than-ideal. Visual: Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images

“Evidence is lacking for the most aggressive measures,” John Ioannidis, a health researcher and evidence-based medicine luminary at Stanford University, wrote in March 2020, in an editorial for a scientific journal. Research on previous respiratory disease outbreaks, he continued, found scant evidence to support practices like social distancing. “Most evidence on protective measures come from nonrandomized studies prone to bias,” he wrote.

Some people in the world of public health fired back: That kind of EBM perspective, they argued, was simply unrealistic in a moment of crisis. “Ioannidis doing his schtick about standards of evidence is not helpful,” Yale epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves wrote on Twitter (now X) that March. “We all want better data,” Gonsalves wrote. “But if you don’t have it. Do you sit and wait for it in a pandemic?”

For people familiar with the history of EBM, the fault lines could sound familiar. Once again, a skeptical group of doctors was challenging medical authority, saying that current practices were based on thin evidence, and warning that the reflex toward intervention might run amok.

Here, though, the challengers weren’t taking on just their fellow clinicians. They were taking on a whole different field: that of public health, and specifically the discipline of public health epidemiology.

In an influential essay for the Boston Review, published in May 2020, Fuller, the Pittsburgh philosopher, laid out what he characterized as a clash of worldviews — a battle between two “distinct traditions in health care” that were also “competing philosophies of scientific knowledge.”

Jonathan Fuller, a physician and a philosopher of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh, has characterized the battle between public health and EBM as a clash of competing worldviews.

Visual: Courtesy of Jonathan Fuller

One of these, he wrote, was that of public health epidemiology. The discipline tried to track and respond to emerging outbreaks by using a whole range of tools, including models and observational studies suggesting that a certain intervention could plausibly have a benefit. This camp, Fuller wrote, “is methodologically liberal and pragmatic.”

On the flip side was the discipline of clinical epidemiology, which, he noted, is closely tied to EBM. That world, he wrote, “tends to champion evidence and quality of data” above all. Its adherents are also usually more conservative about interventions.

It is possible for a single person to draw from both traditions in making decisions. But a clash between those schools of thought, Fuller suggested, was one way to understand some of the emerging flashpoints over the pandemic. At the time, Fuller argued that a synthesis of two approaches might help bolster the pandemic response. He described an approach that would combine the act-now pragmatism of the public health world with some of the skeptical rigor of the EBM mindset.

That synthesis, he reflected in a recent interview with Undark, did not materialize. “I hoped that both of these sides would embrace some of the virtues of the other,” he said.

But it didn’t turn out that way. “If anything,” he said, “I think these two different camps just became more entrenched.”

Recently, some prominent figures in the EBM world have been reflecting on the response to Covid-19. Often, they’ve expressed sympathy for public leaders tasked with stopping a fast-moving pandemic, while also outlining a critique that amounts, in effect, to this: Institutional public health has an evidence problem.

“I empathize with the folks in public health, because their evidence is often low, or very low, quality. And you need to make decisions,” said Guyatt, the McMaster University physician, during a recent Zoom conversation with Undark. But, he argued, public health authorities weren’t transparent about those limitations. “One of the terrible mistakes I think they made,” he said, “was not acknowledging the low quality of the evidence.”

Instead, he and other EBM thinkers have argued, public health authorities overstated the certainty of the evidence behind their decisions. Others have said officials then failed to do the research necessary to actually back up those claims.

“When we actually test them, the majority of things turn out not to work the way we think they should, just because of the complexity of reality,” said Paul Glasziou, a prominent EBM researcher who directs the Institute for Evidence Based Healthcare at Bond University in Australia. Glasziou praised public health leaders for making difficult decisions under pressure. But, as the pandemic wore on, he said, it seemed that public health authorities did too little to try to undertake RCTs and other studies to confirm that measures were working — and to adjust course if not. “It’s not just trials, it was research in general,” he said.

For all of Undark’s coverage of the global Covid-19 pandemic, please visit our extensive coronavirus archive.

Vinay Prasad, a University of California, San Francisco oncologist — and a vocal critic of U.S. public health institutions — was blunter in a blog post published last year. “The issue is not acting without data. We all forgive the initial events of March 2020,” he wrote. “The issue is NOT EVEN TRYING TO GENERAT[E] DATA IN THREE YEARS WHILE YOU TALK AS IF THE SCIENCE IS SETTLED.” Public health leaders, Prasad has argued, should have done more to run RCTs to test whether interventions like mask mandates actually work to slow the spread of Covid-19.

Not everyone in the EBM world is sympathetic to those kinds of arguments. Among them is Trish Greenhalgh, a physician and medical researcher at Oxford, and the author of a popular EBM textbook. She has argued that her colleagues have set unreasonable standards of evidence for public health interventions. She also questions whether RCTs are actually effective tools for studying whether some public health interventions work.

“These methods and tools were designed primarily to answer simple, focused questions in a stable context where yesterday’s research can be mapped more or less unproblematically onto today’s clinical and policy questions,” Greenhalgh and four colleagues wrote in a 2022 paper. “They have significant limitations when extended to complex questions about a novel pathogen causing chaos across multiple sectors in a fast-changing global context.”

In a conversation with Undark in early 2023, Greenhalgh characterized some of her EBM colleagues as becoming dogmatic about RCTs, to the point where they were overlooking other useful forms of evidence. “It’s not everyone in the EBM movement,” she said. “It is the very narrow evangelistic group that have, I think, risen to prominence during the pandemic, and are claiming the EBM kitemark as their own.”

“When we actually test them, the majority of things turn out not to work the way we think they should, just because of the complexity of reality.”

Critics of this segment of the EBM movement have also argued that this intervention-averse, RCT-focused approach has been yoked to political agendas that are increasingly skeptical of certain public health and medical practices.

“I think the structure of public health was stronger in terms of the science than we gave it credit for,” said David Gorski, a physician and an editor of the Science-Based Medicine blog, which has often been critical of EBM. “And it was actively undermined, not necessarily by EBM fundamentalists, but just by ideologues who were not happy with contact tracing, masking, vaccine mandates, public distancing, business closures, et cetera.”

Where some see reasoned medical caution, Gorski and some others describe a kind of weaponized doubt. By constantly demanding higher standards of evidence or not-actually-feasible RCTs, the thinking goes, evidence-based principles can be used to undermine policies at will.

That dynamic, Gorski said, has become potent in the world of medicine for young people experiencing gender dysphoria. There is a lack of RCTs for example, that study the mental health outcomes of certain interventions on patients.

That absence of RCT-oriented evidence has led some EBM leaders to caution against current practices in gender care. “Gender dysphoria treatment largely means an unregulated live experiment on children,” Heneghan told The Times in 2019. Guyatt, more recently, has raised concerns about low-quality evidence in the field. Some critics of current care standards have embraced the EBM label: One of the principal organizations questioning common treatments for minors experiencing gender dysphoria is called the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine.

“I think the structure of public health was stronger in terms of the science than we gave it credit for.”

By the standards of an EBM evidence-rating system called GRADE, “almost all of these recommendations are made on the basis of low quality or low certainty evidence,” said Quinnehtukqut McLamore, a psychologist at the University of Missouri and a close observer of the relationship between EBM and gender medicine. “This sounds bad,” they added, “until you realize that the GRADE guidelines, according to evidence-based medicine, are extremely risk averse. They are very, very strict.”

Many experts say that other, robust forms of evidence show these interventions can help — and that RCTs are an inappropriate tool for studying some of these questions. “RCTs are ill-suited to studying the effects of gender-affirming interventions on the psychological well-being and quality of life of transgender adolescents,” wrote the authors of one 2023 paper, published in the International Journal of Transgender Health. Among other obstacles, the researchers write, patients strongly want the interventions, and will know if they’re not receiving them as part of a study.

At some point, McLamore argued, the drumbeat of concerns about low-certainty evidence shifts from a constructive call for scientific rigor to a kind of politicized obstructionism — one that makes it impossible to act at all.

In 2017, just a few months after finishing a nearly eight-year stint as director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Tom Frieden published an article in The New England Journal of Medicine on the use of evidence in public health. RCTs, he wrote, were not always the best form of evidence to answer vital questions in public health, such as whether taxes can help curb tobacco use. Public health practitioners, he argued, should lean on multiple forms of evidence in making decisions, and avoid fixating on RCTs.

“The goal must be actionable data — data that are sufficient for clinical and public health action that have been derived openly and objectively and that enable us to say, ‘Here’s what we recommend and why,’” he wrote.

In a recent conversation with Undark, Frieden reflected on the fissures between public health epidemiology and EBM. Part of the problem, he argued, was that the EBM movement had taken tools that work well when treating individual patients in the clinic, and tried to apply them in places they don’t belong. A doctor may want an RCT if they’re planning to give a patient a certain drug. But demanding that level of evidence for public health interventions isn’t always feasible, he argued. And the pull toward RCTs can leave people relying on a few bad trials, rather than on higher-quality observational studies, of the kind that are common in public health.

Thomas Frieden, former director of the CDC, sits in the Oval Office during a 2014 meeting with then-President Barack Obama to discuss the government’s Ebola response.

Visual: Kevin Dietsch/White House Pool/Corbis News via Getty Images

Frieden also suggested that, in their skepticism toward interventions, EBM practitioners were at odds with the basic imperatives of public health. In medicine, physicians are trained, above all, to do no harm. In situations of uncertainty, they may default toward inaction. “My father was a wonderful physician and a wonderful cardiologist,” Frieden recalled. “And he was virtually a Christian Scientist when it came to medication.” Unless there was firm evidence, his experience had shown him, giving a drug or some other intervention could cause harm. The situation looks different for practitioners of public health. There, the principle is different: It’s not do no harm, Frieden said, but something more like “above all, avoid a preventable death.”

“That’s a very different ethos,” Frieden added.

Frieden acknowledged that public health decision-making at times relies on imperfect data — something he said could have been more clearly communicated to the public during Covid-19. And at some level, he said public health sometimes requires intuition; it is an art, not just a science. “People who have worked in public health, we have to make decisions in real-time often. And using modeling can be helpful,” he said. “But often, it is kind of an intuitive feel of the data. And I know how unsatisfying that would be for evidence-based medicine people.”

Indeed, Guyatt was not impressed with that reasoning. “Baloney,” he said. “Absolute baloney.”

“Instead of doing that, recognize that it’s low or very low quality, recognize your uncertainty,” Guyatt said. “And then instead of pretending there’s a feel of what is right, make your values and preferences explicit.”

Efforts toward synthesis are underway. “I think Cochrane wants to expand its remit more into public health,” said Lisa Bero, a researcher at the University of Colorado and a longtime member of Cochrane’s leadership.

The move has precedent. In the past 15 years, EBM principles have helped transform another branch of public health, that of environmental health.

Lisa Bero, a longtime member of Cochrane’s leadership, has spent years thinking about how to bridge the worlds of public health and EBM.

Tracey Woodruff, now an environmental health researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, saw the need for those kinds of changes during her time at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in the 1990s and 2000s. Woodruff was skeptical of the way the agency often tackled questions of how, for example, a certain pollutant may affect health. Their methods seemed inconsistent and not always rigorous, she recalled; researchers would gather a batch of studies and make judgment calls about which to focus on in making decisions, rather than having a transparent way of marshaling and organizing data. As a result, she said, evidence was “not evaluated in a consistent fashion.”

Woodruff was part of a push, starting in the 2000s, to bring some of the tools of EBM into environmental health. This specifically meant doing more systematic reviews, in order to have a transparent, consistent way of evaluating evidence.

The work could be uncomfortable for people in the EBM world, who were accustomed to working strictly with RCTs. In environmental health, such trials are often impossible. “You’re not going to do a randomized controlled trial of the effects of PFOA on pregnant women. It’s just not going happen,” said Bero. To answer public health questions, the Cochrane folks had to get used to applying their methods to observational studies and other forms of evidence.

Meanwhile, for people in the world of environmental health, there could be discomfort with the EBM approach — motivated in part, Woodruff said, by concerns that the techniques would somehow downplay or replace expert knowledge. But, she said, the process is akin to expert decision-making, with some added benefits: “It’s a structured approach that you put your judgments together in a way that’s the same — and more consistent.”

Today, those kinds of systematic reviews are more common in environmental health, including as standard practice at federal agencies such as the EPA and in the National Toxicology Program.

Whether similar steps will be taken across public health more broadly is, so far, unclear.

To answer public health questions, the Cochrane folks had to get used to applying their methods to observational studies and other forms of evidence.

When the CDC and other public health leaders, for example, have offered justifications for their support of masking during the pandemic, those documents often resemble a partial list of studies that support mask use rather than a systematic, transparent breakdown of all the available evidence.

On the flip side, a Cochrane review that raised questions about mask efficacy relied exclusively on RCTs that many critics said were simply bad studies, or not well equipped to answer questions about mask use during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Bero, the Cochrane editor, has spent years thinking about how to bridge the worlds of public health and EBM. It’s possible, she said, for Cochrane to maintain its standards for rigor and transparency, while becoming more open to other forms of evidence besides RCTs, and more flexible when tackling complicated questions like those presented by disease outbreaks. “I see us moving towards broader public health questions,” she said. And along the way, she added, “we will inevitably be keeping on this trajectory of diversifying the evidence.”

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.